Expert interview: sustainable food investments in Asia

The rise of the middle class in Asia has led to an ever-increasing demand for high quality, sustainable food. This demand is seen by some as the biggest investment opportunity in the history of capitalism, meaning that massive investment is needed in companies that can source equitably, minimize waste, and streamline the supply chain. Rik Vyverman, the brains behind responsAbility’s equity investments in sustainable food production, has extremely high standards for the companies that he chooses to invest in, and he is now not only seeing the impressive results, but also seeking to dive even deeper into this blossoming arena.

Impact investing in emerging markets can sometimes seem distant, complicated and challenging from the outside. There is also the lingering myth that it exposes investors to too much risk at the expense of not enough return.But that does not have to be the case. According to Rik Vyverman, Head of Sustainable Food Equity at responsAbility, clarity in impact investing, the attractiveness of business opportunities available and the significantly high returns on offer are at the core of quality impact investment.

A Path to Sustainability

After becoming a young multimedia entrepreneur in the 1990s, Vyverman only entered the world of impact investment in the early 2000s after travelling the world. “While I don’t criticise any projects nor their intentions, I believe that the traditional model of intergovernmental development cooperation has made little difference. People progress if they have a job and are paid a decent salary, which requires a robust private sector.”

“With the arrival of a new government in my home country of Belgium, I spontaneously wrote the minister for cooperation a letter, as a private citizen, explaining what I thought Belgium needed and pointed at the relevant instruments for private sector development in emerging markets. To my surprise he invited me to become his advisor and to help implement some of the ideas I had advocated. This led to the creation of the Belgian Investment Company for Developing Countries (BIO-Invest) in 2001, which I ran for four years.”

“I left BIO to set up a private equity fund in Vietnam in 2005 – the SEAF Blue Waters Growth Fund. Vietnam was the final frontier market in Asia at the time. They had just created the legal framework for people to incorporate companies as private businesses. Prior to that reform, the country’s communist system meant that every business was either informal or a state-owned enterprise.”

“I subsequently moved to Switzerland for family reasons and worked as a consultant in private equity investments in emerging markets, for institutional investors, family offices or non-profits until I joined responsAbility in 2013 as portfolio manager and Head of Ventures, before creating the Agricultural equity fund 2017.”

The Food Equity Fund

According to Vyverman, responsAbility has two asset classes, private debt and private equity, and three sectors: financial inclusion, sustainable food and climate finance. “I manage the ‘responsAbility Agriculture Fund I’, which fits in the private equity sustainable food box. Our strategy is to deploy growth capital, focusing on delivering market-based returns, ESG implementation and impact linked to the UN SDGs.”

“The fund has US$67.5 million in committed capital and has been fully invested since November last year, 2 years after it was launched. We are currently raising the responsAbility Agriculture Fund II, which is focused on Asia. Our focus is on the part of food production once crops leave the fields. Agriculture at that stage become more of an industrial or consumer goods activity.”

Asia – The Biggest Opportunity in the History of Capitalism

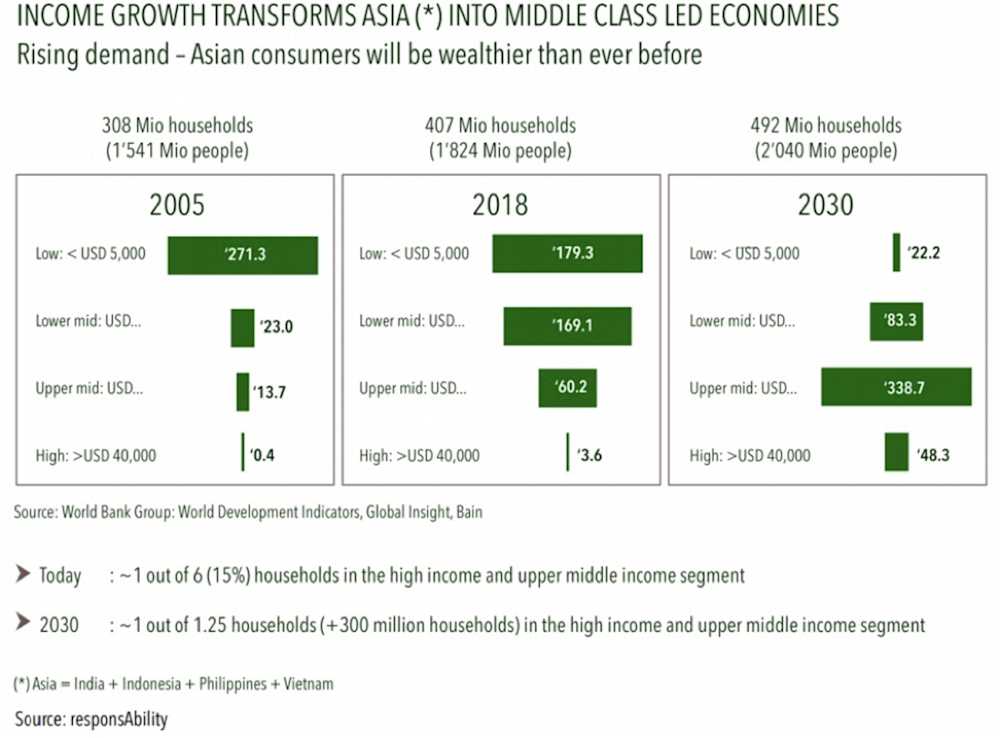

“Asia’s growth opportunity is driven by the rise of Asian consumer and middle class, which according to McKinsey is the biggest investment opportunity in the history of capitalism,” Vyverman says. “According to the 2005 data, 88% of households in Asia’s (ex-China) four most populous countries – India, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines – had an income below US$5,000, the threshold for low income according to the World Bank. By 2018, the share of low-income households had declined to 42%, with lower and upper middle income growing to 56%.”

“According to projections, by 2030 the share of lower or upper middle-income class will reach 95%. The upper-middle class, with incomes above US€10,000, will represent 78% of the population. In ten years’ time, the region will have an extremely large middle-income population.”

This population growth, together with urbanisation and demographic trends will create important demand pressure on the food industry. “This will lead to a tremendous increase in food consumption. The population will become more urbanised too, not only in large metropolitan areas of 10 million people or more, but also of in smaller cities with 500 thousand and 200 thousand inhabitants. The demographics will also change. In 2030 the median age in this region will be 30 years old. Working-age people will be the dominant group. Asian millennials are already better educated and have higher incomes, leading them to have more sophisticated and diverse eating habits, focusing on food safety, health and sustainability, trends which are likely to endure.”

Supply-Side Opportunities

While economic development, urbanisation and population growth are likely to increase demand for agricultural goods, Vyverman is keen to point at the present structure of the region’s agricultural industry to highlight impact investment opportunities. “The supply-side in Asia is a story of small-holder farmers, on average above the age of 55, with typically less than two hectares of cultivated land, uneducated and low use of technology.”

The post-production, service part of the agricultural industry in the region is also plagued by inefficiency, Vyverman says. “While in Europe and in the USA most of the food wastage occurs at the point of consumption, with much food being thrown out by retailers and consumers, wastage in Asia occurs predominantly along the supply chain and processing, as products move from the farms to the consumers.” Vyverman singles out two main problems.

Structurally, markets have been historically disorganized and inefficient, and characterised by layers of intermediaries that don’t add any value to the product but mark-up prices significantly. “Logistically, the inappropriate transportation of food products leads to waste. “On their way to the market, products are often just thrown into a truck without any form of support. Produce will just pile up. Some perishable goods, like fruit will be damaged. In the case of soft fruits, such as bananas, about 15% of the produce would almost automatically be spoiled due to the absence of crates to cushion their transportation,” Vyverman explains. Cold storage is also a problem. “In India, the price of apples drops significantly at the time of the harvests because there are so few refrigerated storage facilities to hold the produce and what doesn’t get sold goes to waste. In Europe, we are able to spread the annual supply of apples because they can be stored in controlled atmospheres and progressively taken to the market for a period of up to 12 months.”

Case Study – Suminter Agrex

“As an investor, this scenario is fertile ground for the introduction of efficient supply chains, methods and technologies that can improve efficiency and transparency,” Vyverman explains. “The consumer benefits from fresh products at lower prices without necessarily hurting the producer. Poverty decreases and tax revenues increase. It’s the definition of a win-win situation.”

As an example, Vyverman cites the investment that the responsAbility Agriculture Fund I made in Suminter Agrex, an agriculture supply chain management company. “The company sells 100% certified-organic, all-natural, non-GMO organic products. They work with over from 60,000 farmers cultivating over 100,000 hectares, without the use of harmful chemicals, delivering high-quality food products. The company has operations in South Asia, Africa and South-East Asia.

The crux of their product is quality assurance and certification, according to Vyverman. “Their products are certified as organic. To ensure this level of quality, the company sends agronomists to visit farmers and teach them how to grow these products. The organic certification process is complicated and involves sampling and testing of every delivery to customers. The company uses a German laboratory to provide these tests in order to use the organic certification of its products.”

“This sort of quality control requires very careful and transparent sourcing and a much closer relationship with primary producers,” he explains. “The company works directly with the farmers and owns local processing facilities. This closer relationship also allows Suminter to share with the farmers a fraction of the premium paid for its goods by consumers.”

The company has been a tremendous success and has seen incredible growth, according to Vyverman. “Suminter has been performing well, in line with the rest of the entire portfolio. The financial return of Fund I is outperforming the upper quartile of European and US PEs and VCs as well as public markets. And even during the COVID-19 pandemic, all our portfolio companies continue to grow by at least 50%, proving the resilience of the companies and more broadly the sector.”

Making an Impact –Simplicity, Performance, Conditionality, and Transparency

When discussing impact, Vyverman is keen to do away with complex terminology. “Clarity and simplicity are paramount. The performance of our investments has to be understandable to clients of a pension fund. It needs to be clear. If we want to continue to see money come into impact investing, be it from institutional or private investors, we should not be making things more difficult.”

On a macro level, the focus of impact investing is to address poverty (SDG1 and 2), climate (SDG12 and SDG13) and economic development (SDG1, SDG6 and SDG11). “Poverty is linked to rural small holder farmers. Climate action is linked to the better use of resources in agriculture. Economic development is linked to job creation, value creation, taxes paid. Impact measurement focuses on certain specific KPIs, such as the number of farmers reached, hectares of farmland under cultivation by sustainable farming, factory output, etc,” Vyverman adds. “We measure these KPIs at the time of investment and project them forwards into the future as we would by the end of the holding period. Throughout the holding period we will report on those KPIs. At the ESG level, we want our companies to operate at the level of international best practices, based on World Bank definitions. At the time of investing we give the companies a rating regarding their operational policy alignment around these ESG issues and throughout the holding period we work with them to improve this score.”

On the topic of governance risks, Vyverman was optimistic. “It’s important to recognize the existence of corruption in any country, and historically its prevalence has been higher in developing countries. However, these countries’ performance in terms of the ease of doing business and corruption has improved a lot over the years.” Moreover, this is not a rubber-stamping exercise. Transparency matters. “For us, the ethics of the entrepreneur we are investing in is key and requires a very thorough due diligence process, including a forensic due diligence on the owners and key management. There is no tolerance for corruption in the companies in the fund. The people that run these companies need to share our values.”

Article originally published here: https://nordsip.com/2020/11/13/tackling-sustainable-food-investments-in-asia/