Analyzing the Climate Phenomenon’s Impact on the Global South

El Niño – A Major Risk to Emerging Markets?

In recent months, global temperatures on land and sea have soared, positioning 2023 as a potential record-breaker.1 While part of a broader global warming narrative, a key player in this year's climatic saga is El Niño. The cyclical disruptor, reappearing after seven years, not only alters weather worldwide but also casts a shadow over various global activities. From agriculture to energy, the stakes are high for Emerging Markets (EM). But how significant are these stakes, and in what ways do they manifest?

Key weather patterns during El Niño

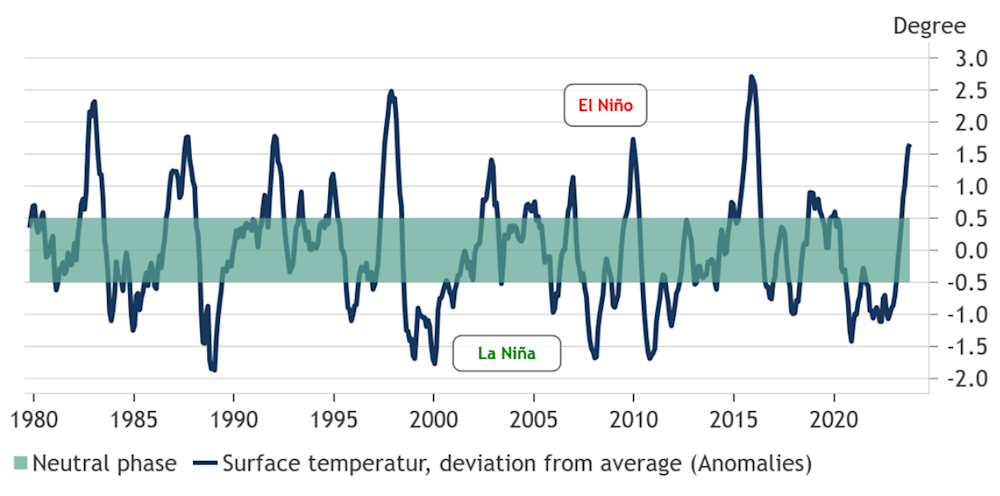

El Niño, part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, alternates between warm (El Niño), neutral, and cool (La Niña) phases, with the cycle repeating every two to seven years. Since 1950, this cycle has punctuated our climate, with notable events in 1965, 1972-73, 1982-83, 1997-98, and 2015-16. The current El Niño, building upon a warmer planet, is poised to make history.2 Meteorologists predict a 70% likelihood of it peaking as a major event by winter, lasting till at least March 2024.3 In this new climate reality, the interplay of El Niño with the positive phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) could bring amplified effects, from heightened global temperatures to altered rainfall patterns.

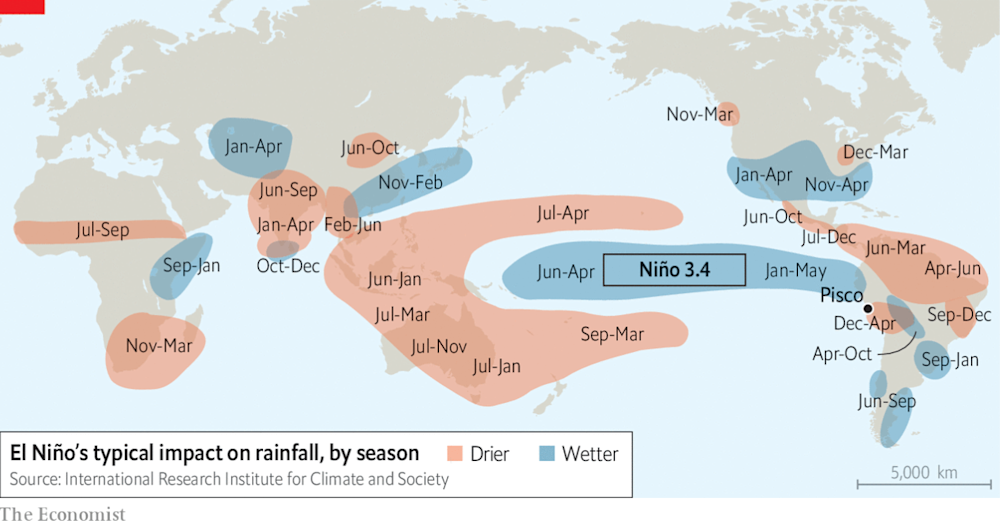

In the current unfolding El Niño phase, which typically spans nine to twelve months, there are notable alterations in rainfall patterns, with some regions experiencing dramatic changes. Traditionally, increased rainfall characterizes areas in southern South America, the southern United States, the Horn of Africa and central Asia. In contrast, El Niño has the potential to induce severe droughts over Australia, Indonesia, parts of southern Asia, Central America, and northern part of South America, as depicted in the map below. The IOD could further accentuate dry weather conditions in Indonesia (and Australia) while reinforcing wet conditions in East Africa. Besides, during the Boreal summer, El Niño’s warm water can act as a catalyst for hurricanes in the central/eastern Pacific Ocean, while it hinders hurricane formation in the Atlantic Basin.

Impact on economic activity and prices

El Niño’s economic footprint is complex and widespread.

Drier conditions in some areas can slash agricultural output, nudging global commodity prices upwards. Peru’s fishing industry, a cornerstone of global fishmeal supply, faces challenges due to shifts in ocean currents. Given Peru’s status of being the largest exporter of fishmeal used in animal feed, lower supply tends to have repercussions on livestock prices.

In regions heavily reliant on hydropower for electricity generation, the impact of El Niño can manifest as power shortages, disrupting activities such as mining. This scenario occasionally has unfolded in Indonesia for example, the world’s largest exporter of nickel -a crucial component for strengthening steel. Consequently, metal prices tend to increase in response to El Niño. Mining operations may also be disrupted by heavy rains, causing infrastructure disruptions, a recurring issue in Chile’s mountainous mining regions, known for their extensive copper deposits.

In Mexico, the East coast, a vital hub for oil production, experiences a decreased frequency of hurricanes. This reduction contributes to an actual boost in oil output there. However, on a global scale, oil and coal prices still tend to increase during El Niño, as these commodities face higher demand due to lower electricity output being generated from thermal power plants and hydroelectric dams.

In light of the aforementioned factors, El Niño is typically associated with upward pressure on inflation. Effects are largest in developing countries, where food prices have a higher weight in consumer baskets underlying the Consumer Price Index (CPI). However, initial conditions play a crucial role; solid crop yields and accumulated inventories in previous years can mitigate some of these impacts. Furthermore, the inflationary pressures on prices tend to be short-lived.

Uncertain impacts, yet certain factors favor adverse outcomes

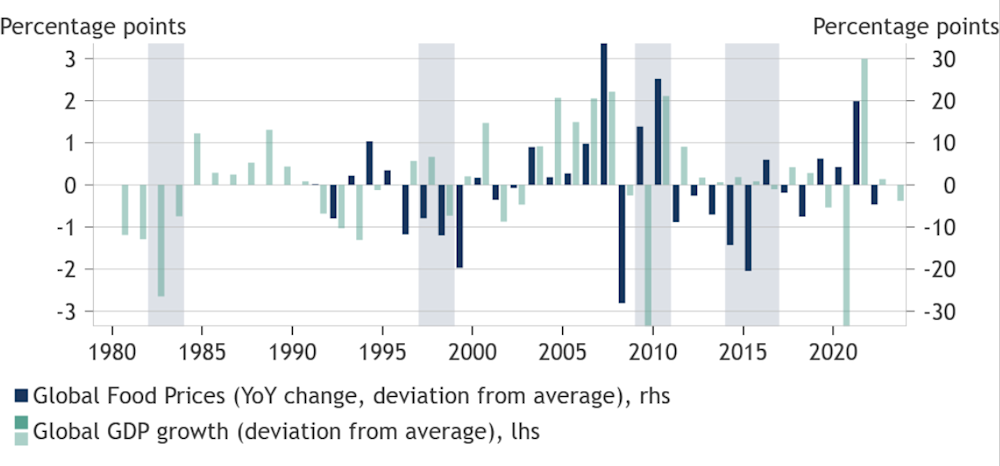

The diverse impacts of El Niño on economies are a subject of ongoing study. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2015 provided crucial insights into to the macroeconomic effects, encompassing 21 countries, across both developed and emerging markets.4 While the IMF’s concluded that the adverse impact on economic activity is mostly short-lived, recent research5 suggests that for a majority of countries, El Niño results in putting activity on a lower growth trajectory. The latter has, however, been criticized for looking at episodes during which other important headwinds where at play, such as El Niño happening during a Fed tightening cycle or the Asian financial crisis. Examining the chart below, in which strong El Niño phases are shaded, there is no clear pattern of global output systematically suffering during El Niño.

On a national level, the magnitude of economic slow down during El Niño events is intricately linked to meteorological impacts and key characteristics of the economy. Key determinants include: a) Primary Sector Size: The smaller, the less a drag on agricultural output will be felt on a national level, b) Economic Diversification: Higher diversification suggesting greater resilience, c) Country Size: Larger geographical areas potentially imply that different areas of the country face different impacts, which might even offset each other - as is the case in China and Brazil, and d) Dependence on Food Imports. Furthermore, countries with fiscal and external buffers will be able to cushion any headwind, not least through additional public expenditures (on food price subsidies, for instance) and/or additional external borrowing.

Which countries are particularly at risk?

While lower income levels are generally associated with a higher importance of the primary sector, lower economic diversification and lesser shock absorption capacity, there is no country where agricultural output systematically dropped substantially during past strong El Niño events.6 Nevertheless, noteworthy deviations for individual years have been observed, reaching up to approximately 20% in some cases. While it is challenging, if not impossible to disentangle the impact of El Niño, it appears to have been a major driver in only a few instances, notably in certain Western and Southern African countries where responsAbility maintains limited exposure.

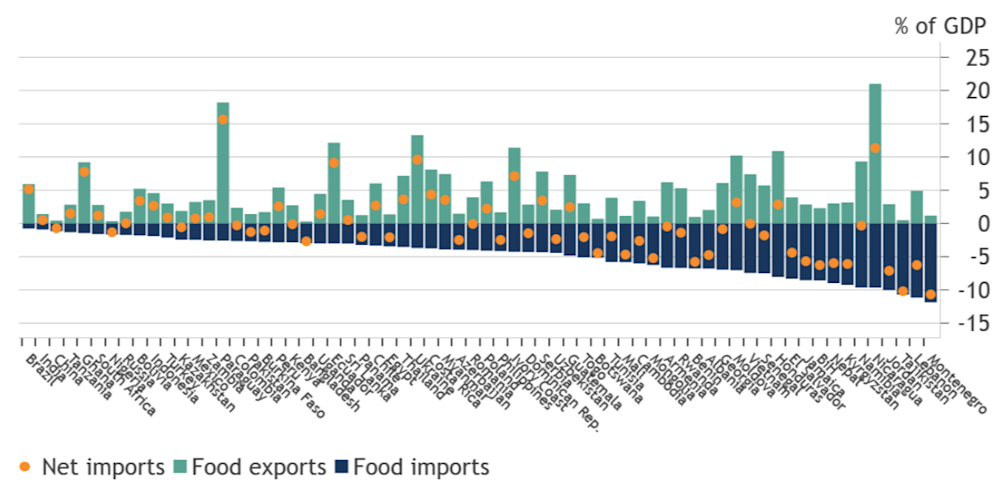

If domestic production does not systematically show large declines due to El Niño, could vulnerability then primarily stem from a dependence on food imports? Clearly, there are numerous countries with a reliance on food imports, most of which can be found in MENA, Central Asia and the Balkans. However, even within this group, only one country lacks clear fiscal buffers capable of cushioning an increase in food import prices - Lebanon. responsAbility has refrained from debt investments ever since the huge political and economic crisis erupted in late 2019.While Egypt and Pakistan also feature in this group, their reliance on food imports is lower than expected, with net food imports amounting to 2.1% and 1.3% of GDP. Furthermore, global food prices have been on a declining trend since peaking in March 2022, and had declined by 11% year-on-year (YoY)by September 2023.

Might the economic setback originate from weather-related disruptions in the mining sector? Looking at historical patterns, no country in our investment universe shows a combination of a high reliance on mining and large drops in mining production during past strong El Niño events. The nation closest to embodying this combination is Chile, as previously noted, where intermitting heavy rains have sporadically disrupted mining activity. Even in this context, responsAbility maintains minimal exposure to Chile.

Lastly, assessing the impact of El Niño hydropower, the availability of data on the importance of hydropower presents a challenge, with comprehensive information only being accessible for roughly one-third of countries. Within this limited small sample, a few markets show a combination of drier weather conditions and a reliance on hydropower. Those markets include Colombia and Vietnam.

In Colombia, hydropower constitutes approximately 80% of total power generation. Because of this vulnerability, the country has taken measures, acknowledged by Moody’s as “significant steps” to protect power generation against El Niño related damage by adding amongst others gas-fired power generation. It is pertinent to note that, while electricity prices have showed quite a marked increase since 2022, the pace of price increases has slowed substantially since October 2022.

Meanwhile in Vietnam, hydropower contributes to “only” roughly one third of total power generation. With the country suffering from an unprecedented drought, several hydropower plants had to close down around mid-2023, causing power shortages in an environment of rapidly rising electricity demand. According to the World Bank, the economic costs of these outages were around 0.3% of GDP. Since, the situation has improved somewhat, not least thanks to heavy rainfalls in July.

Conclusion

In summary, although El Nino disrupts the climatic equilibrium, its economic ripple effects on Emerging Markets are nuanced. For most, the impact might be muted, thanks to a blend of natural resilience and strategic mitigations. Yet, for a few, the challenges posed are real and pressing, demanding a calibrated response.

Sources:

1 World Meteorological Organization (WMO): September smashes monthly temperature record, Press Release as of 5 October 2023, see here

2 The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration sees a 66% probability, see here. 3 NOAA: September 2023 ENSO Outlook, see here. 4 IMF (2015): Fair Weather or Foul? The Macroeconomic Effects of El Niño. Working Paper WP/15/89 5 Callahan & Mankin (2022): Persistent effect of El Niño on global economic growth 6 The maximum we get in terms of average annual downward deviations from trend agricultural output during the past four strong El Niño is 6.5%, which is for Namibia.

Philipp Waeber

Philipp Waeber is responsAbility’s Chief Economist. With 15 years of experience in macroeconomic analysis, he has a wealth of experience in assessing major contextual risks to our investments and guides investment decisions in challenging markets. While often working on specific countries, he keeps the bigger picture in mind and occasionally writes about it, as in the article above. Philipp has a bilingual master’s degree in economics and is a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) charterholder.