From Credit to Capability: How Finance Fuels Development

Nearly ten years ago, while travelling in Sri Lanka — a trip I would think twice about today for climate reasons — I met a tuk-tuk driver who had recently taken a loan to buy his vehicle. The repayment period was just three years, which struck me as potentially burdensome. Yet he was proud: the tuk-tuk allowed him to earn a stable income, support his family, and build something of his own.

That short conversation captured a simple truth: when finance is accessible and productively used, it can transform lives. A loan is not just a liability; it can be a bridge to opportunity. And his story is not unique. It reflects a broader pattern economists have observed for decades: when financial systems channel capital effectively, the benefits extend far beyond individuals—they shape how entire economies grow and evolve.

A strong financial system does far more than move money. It shapes how people live, how firms grow, and how economies transform. When finance works well, households can manage shocks, entrepreneurs can build businesses, and countries can accelerate sustainable development. When it doesn’t, opportunities stall and inequality widens.

Across emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), the lessons from recent decades are clear: finance fuels development, but only when supported by strong institutions, sound policies, and thoughtful innovation.

Core Functions of the Financial System

A well-functioning financial system is essential for channelling resources to their most productive uses and supports economic growth. Research such as the comprehensive review by Ross Levine (2004) shows that financial systems support development through several essential functions:

Mobilizing and pooling savings: Financial institutions collect savings from households and firms, making these resources available for investment.

Allocating capital efficiently: By gathering and analyzing information, financial intermediaries and markets help direct funds to the most promising investment opportunities.

Improving corporate governance: Financial systems help ensure that managers use funds responsibly. Through monitoring, reporting requirements, and incentives, they reduce agency problems—that is, situations where managers (agents) may not act in the best interests of owners or lenders, and align interests between lenders, owners, and managers.

Facilitating risk management: By offering tools for diversification, insurance, and hedging, financial systems allow firms and households to manage uncertainty. This supports innovation and long-term investment, especially in economies vulnerable to shocks.

Easing the exchange of goods and services: Efficient payment systems and financial innovation lower transaction costs and support specialization and trade.

Taken together, these functions help economies allocate capital where it creates the most value—to people, firms, and sectors that can drive long-term development. They determine whether a small business can scale, whether farmers can survive a bad season, and whether workers can invest in education and mobility.

What Enables Financial Development? Institutions First

Financial development depends heavily on institutional quality: the protection of property rights, the enforceability of contracts, the strength of creditor rights, and the clarity and predictability of regulation. Between the mid-1980s and early 2000s, many EMDEs liberalized their financial systems by loosening restrictions on credit allocation, interest rates, and foreign bank entry, and by increasing capital account openness. However, as the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s demonstrated, liberalization without sound regulation and supervision can create fragility rather than stability. The lesson: financial liberalization works best when paired with robust regulation, supervision, and the rule of law.

Macro-Financial Stability: Substantial Progress in EMDEs

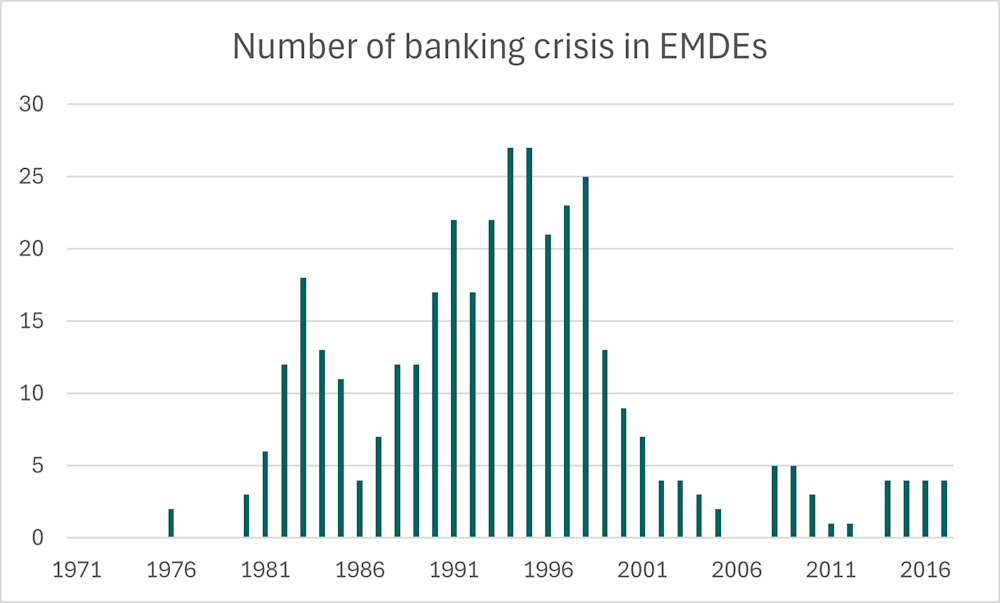

Since the late 1990s, EMDEs have achieved substantial gains in macro-financial stability. Banking crises have become less frequent, regulatory frameworks have improved, and monetary policy has become more credible. Central banks have greater independence, and policy approaches to managing capital flows and exchange rates have matured. Nevertheless, the quality of regulation and supervision still varies widely among EMDEs.

Empirical evidence from cross-country and firm-level studies confirms the impact of finance on growth. Countries with more developed financial systems tend to grow faster, accumulate more capital, and achieve higher productivity. This relationship is robust even after accounting for other factors such as education, trade openness, and macroeconomic stability. Finance helps firms overcome external financing constraints, supports entrepreneurship, and enables technological innovation.

When Finance Supports Growth—and When It Doesn’t

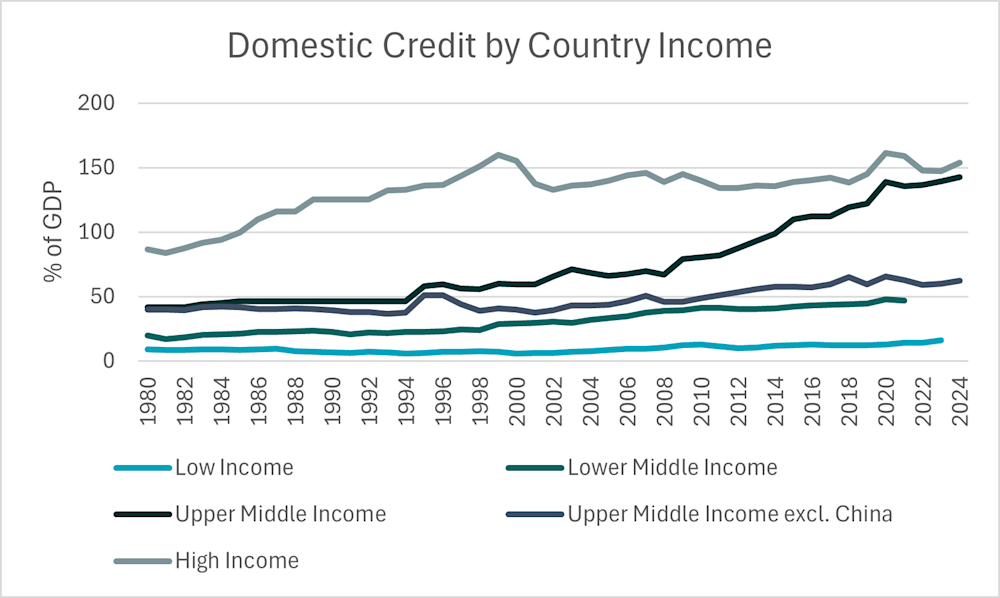

Finance has the greatest positive impact on growth when development is moderate. In contrast, in overleveraged markets—where credit expands far beyond the needs of the real economy—additional finance can lead to instability and even lower growth. According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, 2024), once the credit-to-GDP ratio exceeds 100%, further credit tends to flow to borrowers who already have ample access, rather than easing constraints for underserved.

Most EMDEs remain well below this threshold. This is evident when looking at domestic credit by income group: while high-income economies average around 150% of GDP, upper-middle-income countries excluding China stand at roughly 62%, and lower-income groups remain even lower. Excluding China is essential; its scale and leverage distort the global picture. Overall, EMDEs have considerable room for further financial deepening without approaching overleveraged territory.

Finance as an enabler of the SDGs

Financial development is closely linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Financial inclusion, in particular, is explicitly mentioned in two targets: United Nations SDG 1.4, which calls for universal access to financial services, and SDG 8.10, which urges the strengthening of domestic financial institutions . Its contribution, however, extends well beyond these formal references. Expanding financial access fosters entrepreneurship and job creation, reduces poverty and inequality, and strengthens resilience, supporting progress on the SDGs 1 (No Poverty), 5 (Gender Equality), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and others. Finance is therefore not an end in itself but a cornerstone of inclusive and sustainable development.

Further Room for Financial Deepening

Despite progress, significant gaps remain. Micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which form the backbone of EMDEs, face a persistent—and growing—financing shortfall. The International Finance Corporation (IFC, 2025) estimates that this gap reached USD 5.7 trillion in 2019, equivalent to 19% of GDP. Roughly 40% of formal MSMEs in EMDEs are credit-constrained, with women-owned businesses particularly underserved.

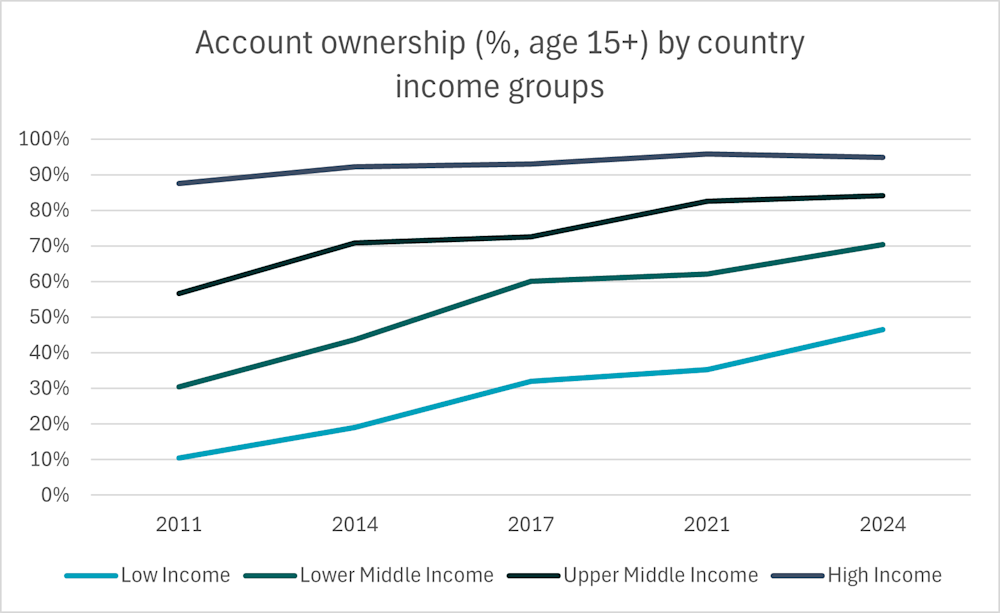

At first sight, the picture for households looks somewhat different, with account ownership having greatly increased over the past 15 years, see chart below. Even so, account ownership in EMDE still trails behind that of advanced economies, and usage lags behind access. Financial development still has considerable room to advance.

Digitalization: Transforming Access and Inclusion

Digital innovation has reshaped financial inclusion. Mobile banking, fintech platforms, and alternative data have expanded access to credit and payments for populations previously excluded from the formal financial system. These innovations reduce costs and physical barriers.

But digitalization also brings new challenges—such as the need for updated regulation, data privacy, and digital literacy. With sound policy and investment in digital infrastructure, these risks are manageable, and the overall impact is overwhelmingly positive. Digital finance is accelerating inclusion, lowering transaction costs, and fostering a wave of innovation across EMDE financial sectors.

Finance as an Engine for Development—But Not a Panacea

Financial sectors are fundamental to development. They underpin growth, poverty reduction, and resilience. Yet, the experience of EMDEs shows that financial deepening must be accompanied by sound regulation. Most EMDEs still have significant room to expand access, strengthen inclusion, and deepen financial markets. At the same time, policymakers must remain vigilant to the risks of excessive credit growth. The goal is not simply more finance, but better finance: systems that translate financial deepening into broad-based, sustainable development.

It is ultimately about ensuring that millions of people, each with their own ambitions, like the tuk-tuk driver I met, can turn access to finance into opportunity.

References

Levine, R. (2004). Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence. NBER Working Paper No. 10766.

Bank for International Settlements (2024). Keeping the momentum: how finance can continue to support growth in EMEs.

International Finance Corporation (2025). MSME Finance Gap: An updated Estimation and Evolution of the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Gap in Emerging and Developing Markets.

Klapper, L., Singer, D., Starita, L., & Norris, A. (2025). The Global Findex Database 2025: Connectivity and Financial Inclusion in the Digital Economy. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Philipp Waeber

Philipp Waeber is responsAbility’s Chief Economist. With 15 years of experience in macroeconomic analysis, he has a wealth of experience in assessing major contextual risks to our investments and guides investment decisions in challenging markets. While often working on specific countries, he keeps the bigger picture in mind and occasionally writes about it, as in the article above. Philipp has a bilingual master’s degree in economics and is a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) charterholder.