No, It’s Not Too Late: Debunking Five Climate Myths Fuelling Inaction

The science around climate change continues to sharpen our understanding of both the risks ahead and the solutions already within reach. Yet, misconceptions about climate change and climate action remain widespread. These debates unfold amid missed or crossed climate milestones, political shifts, and challenging market conditions, which can make it harder to see what still matters and what is possible.

This article explores some common climate myths and examines what the evidence actually shows. By breaking complex topics into short, accessible insights, it aims to provide clarity and context and highlight that meaningful pathways forward remain open.

Myth 1: “We’ve missed the 1.5°C target, what’s the point now?”

Temperature records show that 2024 reached an annual average of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This is a serious milestone, but does it mean the Paris Agreement target is a lost cause? And if so, why should we bother to keep on fighting climate change?

The 1.5°C temperature goal refers to long-term warming, not a single year.1 The UN Emissions Gap Report (EGR) 2025 notes that the world is very likely to exceed the 1.5°C limit in the near future. However, the report also emphasizes that continuing efforts remain essential to limit the temperature overshoot to a minimum.2 What matters now is how high and how long the overshoot lasts. This is crucial because the Earth’s climate is not a binary system and the impacts of climate change escalate with each fraction of a degree. Recent research illustrates this sensitivity:

The IPCC’s 6th assessment report (AR6) confirms that extreme rainfall and heat events become more frequent with temperature rise.3 A more specific example finds that in Western Europe, flood frequencies increase from 22% in a +1.5°C world to 33% in a +2°C world.4

Food systems show a similar pattern. Moderate warming may temporarily increase global yields of wheat and soy due to a larger production in higher latitudes and a ‘fertilization effect’ from higher CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere. Yet this trend reverses with a 2°C temperature rise, leading to a decrease in global production capacities.5

This context explains the significance of António Guterres’ remarks at COP30. He emphasized that science now shows a temporary overshoot of 1.5°C is unavoidable due to decades of insufficient action. However, he also stressed that this does not mean the world has lost the ability to act. With rapid and sustained mitigation efforts, global temperatures can still decline later this century. The key is to keep the overshoot as limited and short-lived as possible so that risks remain manageable. His message captures the central point: climate change is not a single threshold that, once crossed, determines all future outcomes. It is a spectrum of risks, and every decision taken today influences the future trajectory.

Myth 2: “Climate change will hinder economic growth because decarbonization is too expensive.”

It is true that fossil fuels were central to economic development by powering transport, generating electricity, and enabling industrial processes. As a consequence, developed economies have grown in sync with global emissions. However, the belief that emissions and economic growth must always move together is no longer accurate. Additionally, multiple studies show that inaction is far more costly than mitigation:

Climate change-related health issues alone are projected to cost USD trillions each year, according to the World Bank.6

A study led by the Boston Consulting Group estimates that limiting warming to below 2°C requires investments of 1%-2% of cumulative global GDP, yet this would avoid economic damages equal to 11% to 24% of global GDP.7

The OECD finds that climate action increases productivity and innovation, which results in long-term economic benefits.8

Transitioning not only avoids costly consequences of fossil fuels, but low-carbon technologies are also starting to be more cost effective than their fossil fuel-based alternatives. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) confirmed in a 2024 report that 91% of new renewable electricity projects deliver electricity at a lower cost than their fossil fuel-based counterparts, and that large-scale solar PV production was 41% cheaper than fossil fuel-based alternatives.9

There is growing evidence that the previous relationship between prosperity and emissions is changing. In the EU member countries economies grew by 66% between 1990 and 2023, while emissions decreased by 30%. Similarly, GDP in the US has doubled since 1990, despite the dropping CO2 levels to those seen in 1990.10 And it’s not only developed economies that are seeing the potential of shifting their economic activities to low-carbon alternatives. Many policy makers across emerging economies have long seen the potential and opportunities in building low-carbon economies as best summarized by Ms. Dima Al-Khatib, Director of the UN Office for South-South Cooperation: ‘South-South and triangular cooperation are not only development modalities – they are the engines of resilience, adaptation, and innovation’.11

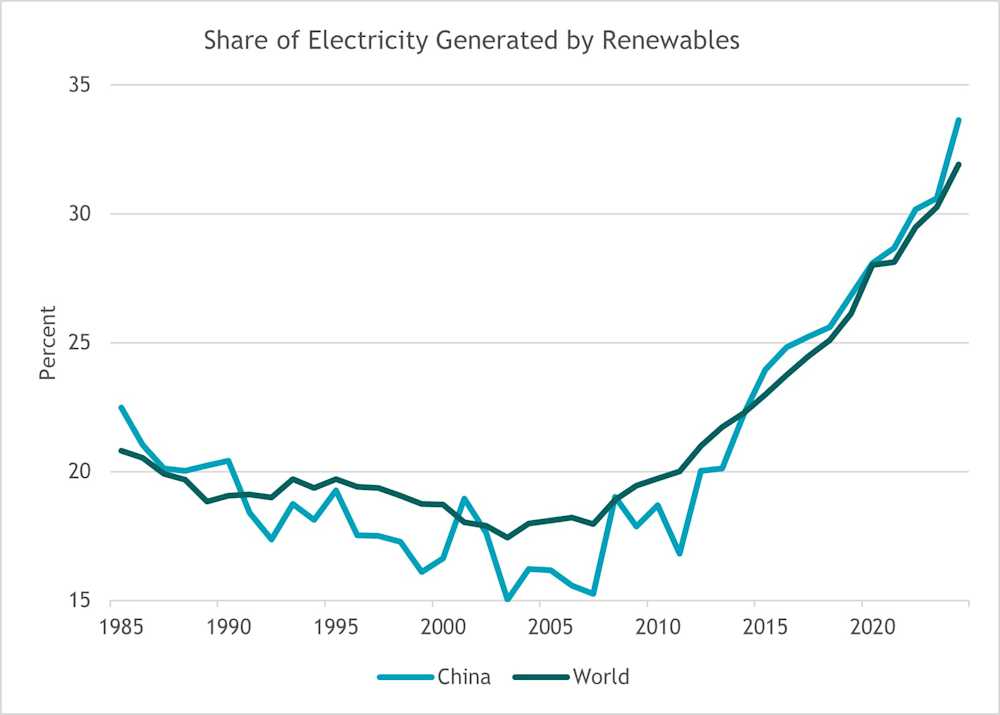

Brazil announced a R$107 million commitment to strengthen bioeconomy value chains in the Amazon, with the aim to preserve the region while increasing climate resilience and generating income and new jobs.12 China illustrates how climate action can align with economic strategy. After long viewing emissions cuts as a threat to growth, the country shifted in the mid-2010s to treat the energy transition as an industrial opportunity.

Today, China is the world’s largest installer of wind and solar power and supplies an estimated 60–80 percent of global solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and lithium-ion batteries. This scale has driven costs down, strengthened export competitiveness, and supported domestic industries. While China remains the world’s largest emitter and its climate action is driven by economic pragmatism rather than virtue, its experience shows that sustained investment in low-carbon technologies can enhance growth, competitiveness, and energy security rather than constrain them.13

Myth 3: “We’ve got time! Future tech will fix it.”

There are promising technologies that can remove CO2 from the atmosphere such as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) and Direct Air Capture (DAC), as well as nature-based solutions like reforestation. This raises an important question: can we rely on emission removal technologies instead of prioritizing emission reductions? Scientific review and industry experience show that many challenges remain for the deployment of technologies such as DAC. Recent studies highlight several persistent barriers, including high costs driven largely by enormous energy demand, lower-than-expected efficiencies, concerns about the long-term storage of captured CO2, and regulatory uncertainties.14,15 Together, these factors have contributed to the slow scaling of engineered carbon removal technologies over recent decades.

In reality, their contribution to total net emissions, compared to nature-based solutions like afforestation remains very small15 and is currently estimated at a mere 0.1% of global emissions.14 The International Energy Agency (IEA) notes that progress varies across technologies, and identifies effective market mechanisms and advancing policies among crucial levers to accelerate scaling.

Does this mean that carbon removal technologies simply need more time to deliver at scale? In practice, relying on this approach would be a high-cost gamble that risks delaying the deployment of already proven climate solutions. One key reason is the way the climate system responds to change. The climate reacts with a lag, an effect known as ‘climate inertia’. Even if global emissions were stopped immediately, temperatures and other climatic changes would continue to rise for some time.16 Consequences such as biodiversity losses, health impacts, and sea level rise are therefore already partly locked in by past and present emissions and cannot be fully reversed through future carbon removals.

But the good news is that more effective and affordable options are already available. Technologies with costs of USD 100 per ton of CO2 equivalent or less are available to reduce emissions by half relative to 2019-levels by 2030, and measures costing below USD 20 per ton account for more than half of this potential.17 Carbon removal technologies will still play an important role, but their role is specific. They are best suited to addressing residual emissions from hard-to-abate sectors such as aviation and heavy industry, and to enabling net-negative emissions in the longer term. They are not a substitute for deep and immediate emission reductions.

Myth 4: “Now is not the right time for climate action. Politics are too unstable and individual impact is limited.”

As climate action faces headwinds, it can leave a feeling of powerlessness that makes delaying action an appealing strategy. However, it is not an economically sensible one. Every year of delayed climate action increases future costs by an estimated USD 0.6 trillion.18 The same logic applies at the corporate level. A ‘wait-and-see’ approach is a strategic risk. Businesses that postpone their transition risk losing competitiveness and becoming less resilient as global markets continue to change,19 regardless of what administration is in power.

Political leadership plays a crucial role, which is something we as individuals can influence through voting. Voting shapes climate policy, and research shows that political shifts often follow when climate becomes a decisive issue for voters. Individual behavior also drives market transformation. Many large-scale changes, such as widespread solar adoption or the growth of electric vehicles, began with small groups of early adopters. Personal choices help signal demand to companies and policymakers. Climate action is not about achieving perfection, but about creating momentum through collective behavior.

Myth 5: Climate change is natural – it’s always been this way

Yes, the Earth’s climate has always changed, however the current rate of warming is far beyond natural variation. Amongst natural factors that drive long term temperature shifts are the Milanković cycles, which reflect slow changes in Earth’s orbit, tilt and axial rotation.20 These cycles influence the amount of solar radiation our planet receives, yet they occur over tens to hundreds of thousands of years not centuries or decades as we’ve been experiencing the current global warming.21

If the Milanković cycles were the dominant driver of today’s global warming, our planet would currently be cooling rather than warming. Climate models show this clearly. Simulations that include only natural drivers cannot reproduce the rapid warming observed since the mid-twentieth century. Only when anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are included do the models align with real-world temperature observations.22

Distinction between weather and climate matters. Weather describes short-term conditions we experience of the atmosphere characterized by temperature, wind, precipitation, etc. Climate, however, is the average of those conditions measured over a longer period, typically 30 years.23,24 Short-term variability of the weather is normal including cool days and even seasons. The persistent and sharp upward trend in global temperatures and rapid change in climate on the other hand is not.

Where this leaves us

The science around climate change continues to sharpen our understanding of both risks and solutions. While misconceptions endure, evidence shows that the future is not predetermined. Decisions taken today influence the scale of impacts tomorrow, and many effective tools are already available. Looking ahead, this leaves room for cautious confidence: it is not too late, and meaningful progress remains possible. The coming years still offer opportunities to move toward more sustainable and resilient systems.

1 Bevacqua, E., Schleussner, C.-F., & Zscheischler, J. (2025). A year above 1.5 °C signals that Earth is most probably within the 20-year period that will reach the Paris Agreement limit. Nat. Clim. Chang, 15, 262–265. 2 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2025). Emissions Gap Report 2025: Off Track – Continued collective inaction puts global temperature goals at risk. Nairobi. 3 Seneviratne, S. I., et al. (2021). Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. 4 Fang, B., Rakovec, O., Bevacqua, E., et al. (2025). Diverging trends in large floods across Europe in a warming climate. Commun Earth Environ, 6, 717. 5 NASA Science. Why a half-degree temperature rise is a big deal. 6 World Bank. (2024). The Cost of Inaction: Quantifying the Impact of Climate Change on Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Washington, DC. 7 Benayad, A., Hagenauer, A., Holm, L., Jones, E. R., Kämmerer, S., Maher, H., Mohaddes, K., Santamarta, S., & Zawadzki, A. (2025). Landing the economic case for climate action with decision-makers. Boston Consulting Group. 8 UNDP. Investing in Climate for Growth and Development 9 International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). (2024). Renewable power generation costs in 2024 – Executive summary. 10 International Energy Agency (IEA). The relationship between GDP growth and CO₂ emissions has loosened – and needs to be cut completely. 11 United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation (UNOSSC). From Marrakech to Belém: High-Level Global South Dialogue amplifies Southern leadership in shaping the climate agenda. 12 Government of Brazil. (2024). Brazil announces R$107 million to boost the Amazon bioeconomy at COP30. 13 The Economist. The world’s renewable-energy superpower. 14 Rasool, M. H., & Hashmi, S. A. M. (2025). Carbon capture and storage: An evidence-based review of its limitations and missed promises. 15 Meehan, D. N. (2025). Risks and challenges in CO₂ capture, use, transportation, and storage. 16 Climate System Inertia → Term 17 IPCC. (2022). AR6 Working Group III – Summary for Policymakers. 18 Sanderson, B. M., & O’Neill, B. C. (2020). Assessing the costs of historical inaction on climate change. 19 Global Commission on Adaptation / WEF (or similar). Wait-and-see is not an option to ensure future climate resilience. 20 NASA Science. Milankovitch (orbital) cycles and their role in Earth’s climate. 21 NASA Science. Why Milankovitch cycles can’t explain current global warming. 22 The Environmental Literacy Council. Do Milankovitch cycles explain climate change? 23 World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Weather. 24 World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Climate.

Christine Bürgi

Christine Bürgi is a Climate Impact Specialist at responsAbility. In her role, she evaluates and quantifies the climate impact of companies and actively researches emerging trends in climate science, technology, and global climate policy to inform our investment strategies in climate change mitigation and adaptation. Christine earned her master's degree in Environmental Sciences, specializing in Climate and Atmospheric Sciences, from ETH Zürich.